EPICS

I work in the Control Systems Group at Diamond Light Source. The core of that group's responsibilities is the control system, used to allow people and software to control and monitor how the accelerators and scientific equipment behave.

Central to the control system is a software toolkit, nominally the Experimental Physics and Industrial Control System, but universally known as EPICS. This encompasses embedded software to control real devices (magnets, vacuum pumps, motors), logic about how these should work, transmitting that information across the network and being able to control those devices from so-called client machines.

Most of the work in the Control Systems group involves interacting with one of these parts of EPICS.

Client-Server Architecture and Distributed Control

Computing is full of what are known as clients and servers. A server provides some service: it could provide HTML to be rendered in a web browser, data from some database, map tiles, or basically anything else. A client uses one or more of these services, and the machine reading this web page is an example of one of these clients.

EPICS is a distributed control system. What this means is that there are many servers, typically one for a discrete part of the control system, and there are many clients reading from these many servers.

IOCs and PVs

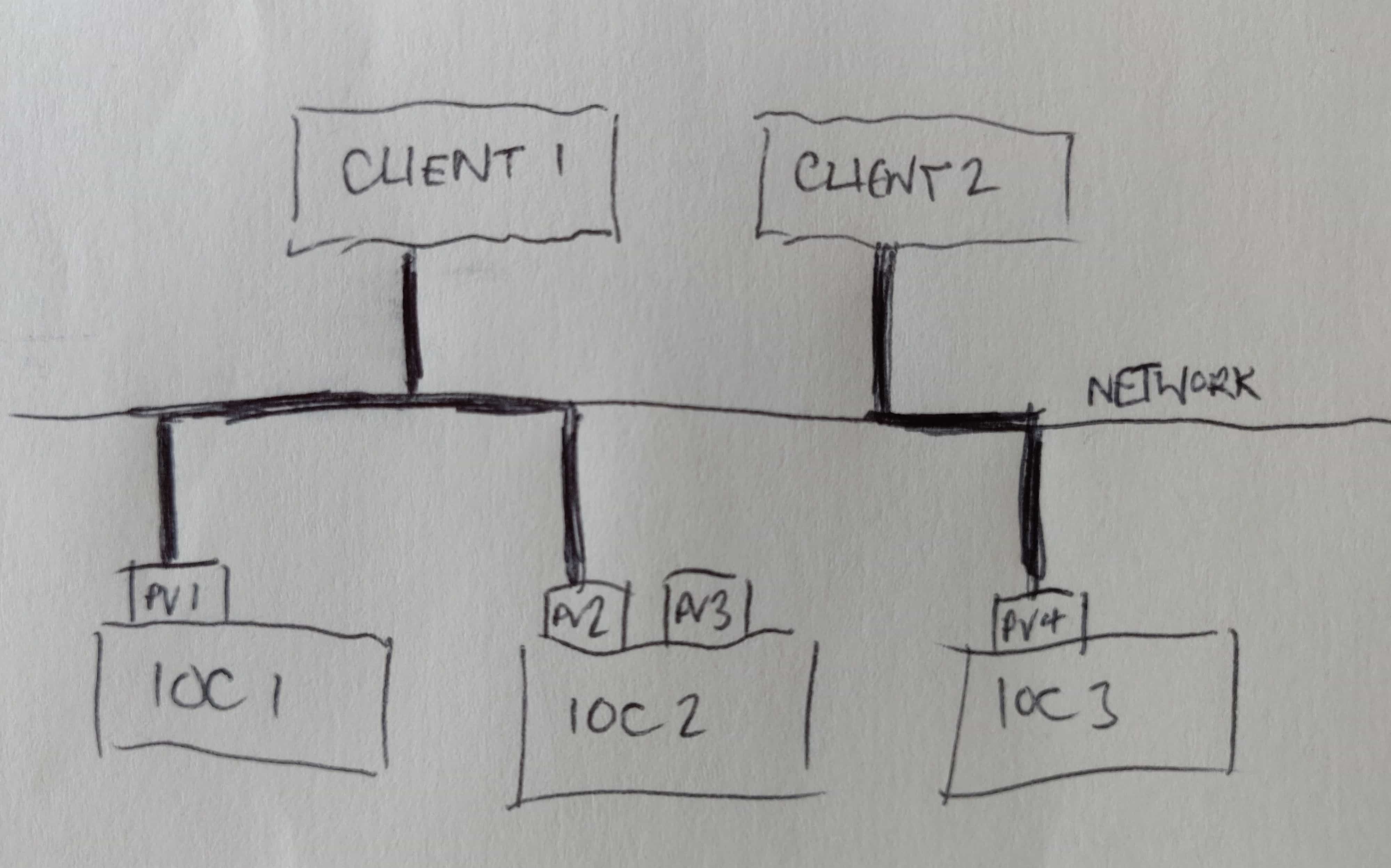

EPICS servers are called input/output controllers or IOCs, for reasons that may or may not make sense. Each IOC provides a number of process variables or PVs. A PV represents one value, often a physical quantity such as a temperature, voltage or current in a device, but just as likely some more abstract but useful value. EPICS allows you to read from and possibly write to this value from anywhere on the control system network.

A schematic view of an EPICS control system, including clients, IOCs and PVs. The thicker lines suggest that client 1 is connecting to PV1 and PV2, and client 2 is connecting to PV4.

To illustrate this, at Diamond it would be easy to go to the Control Room, log into one of the Control Room Linux machines and write an incorrect value to the PV that represents the current of one of the magnets in the accelerator. This would promptly change that current in the real magnet, divert the electrons from where they ought to be, and 'dump the beam'. Don't do this.

Datatypes

EPICS up to version 3 (later versions are described in this somewhat more technical post) uses relatively simple datatypes. A PV's primary value may be an integer (of different sizes), float, double or an array of these. These PVs may have additional metadata that is relevant for a control system, such as an alarm status (typically used to show the yellow or red LEDs that you see on the classic control system UIs).

(There are a couple of other types available, enums and strings, that aren't particularly interesting at this stage).

The EPICS Client

The EPICS client is simple. All it needs to do is understand the data that needs to be sent and received over the network, and convert it into a format useful for the user or application. The main complexity is managing waiting for the network responses, which must be handled intelligently by the client applications.

You can use this information to create the classic control system user interfaces with green, yellow and red LEDs that you might see in a film.

The Network Protocol

Fundamental to how EPICS works is the way that clients and servers interact over the network. This is described in the EPICS network protocol, which is called Channel Access. There are a number of parts to the protocol:

- finding the IOC that provides the PV you are interested in

- establishing a connection to the IOC

- requesting single values for the PV

- registering interest in updates from the PV

- setting values to the PV

- announcing that the IOC is available

All of this is implemented on top of the TCP and UDP protocols that you already use when browsing the internet.

In practice, the details of the protocol are handled by code in different programming languages, and it's only useful to know when you are debugging problems with channel access itself, which is comparatively rare. However, some aspects are useful for understanding the principles of the control system.

IOCs

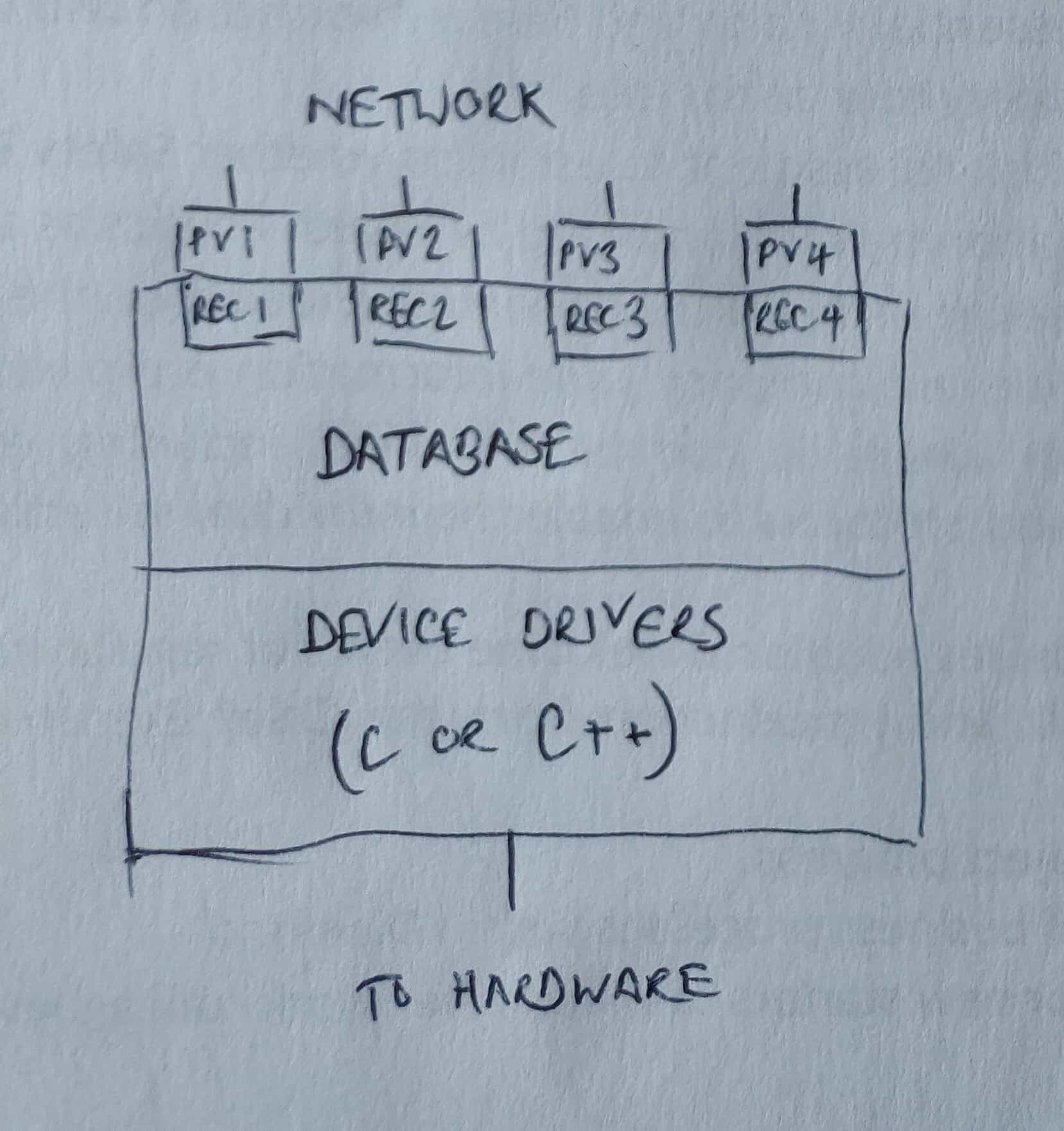

Much of the complexity in EPICS comes from code in the IOCs. This can broadly be separated into two parts:

- communication with the hardware itself

- the 'database', of a type specific to EPICS and not to be confused with relational databases such as Oracle

The database is used to define the names and types of the PVs that are used by the higher levels of the control system. There is also a certain amount of logic built in to the database, so that you can define how different variables interact with each other. (Strictly, in the database you define things called 'records', but for the purposes of this post you can think of these as the same as PVs.)

Below the database there is custom code that allows you to connect those variables to the real hardware that you are trying to control. This comes in many forms; the EPICS community has already written drivers for many types of device.

A schematic view of an IOC.

Once these parts are in place, if you configure your software and hardware correctly you can run your IOC and it is then available to be controlled over EPICS.

The Control System

At Diamond, each part of the control system comprises some number of IOCs available on the network. These IOCs may communicate with each other using channel access; the client software also connects with the IOCs over channel access.

The distributed nature of EPICS means that more IOCs can be added to the control system without changing anything else, and they are available immediately. This behaviour scales very well as the control system grows, the main limitation being the capacity of the network on which it is running.

This has one problem: if you accidentally define two PVs with the same name EPICS cannot distinguish them and you cannot define which one you would like to control. Design discipline is the best way to avoid this problem. With a large facility like Diamond, which has more than one million PVs, this discipline must be rigorous.

However, if you get some basic principles right, EPICS can give you a control system that will scale up to the largest scientific facilities and work very reliably. It has served Diamond well for the past 15 years and we expect it to continue to do so.